Beyond the Black Box: Japan's Digital Kabuki Revival

Japan's ancient dramatic art form of Kabuki is experiencing an unexpected renaissance in the digital age. Traditional performances with centuries-old techniques are finding new life through cutting-edge technology, creating hybrid experiences that honor historical traditions while embracing modern innovation. This cultural phenomenon represents a fascinating intersection of preservation and evolution, attracting younger audiences previously disconnected from their theatrical heritage. The digital Kabuki movement raises important questions about authenticity, cultural legacy, and the future of traditional art forms in an increasingly technology-driven world. Artists and cultural institutions must navigate these complex waters as they strive to keep Kabuki relevant without losing its soul.

The Storied Legacy of Kabuki Theater

Kabuki theater emerged in early 17th century Japan, beginning with female performer Izumo no Okuni’s dances in Kyoto’s Kamo River dry beds. These performances quickly gained popularity but faced government regulation when authorities banned women from performing, concerned about moral implications and connections to prostitution. This restriction gave rise to the onnagata tradition—male actors specializing in female roles—which remains a distinctive feature of Kabuki today. Through the Edo period (1603-1868), Kabuki flourished as entertainment for commoners, developing elaborate staging techniques, stylized acting methods, and distinctive makeup called kumadori. The art form established key performance elements including mie (dramatic poses), danmari (silent pantomime), and aragoto (rough, exaggerated style), creating a theatrical language that has endured for centuries. Despite periods of decline, Kabuki was recognized as an Important Intangible Cultural Property in 1965 and listed as UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage in 2005, affirming its significance in global cultural history.

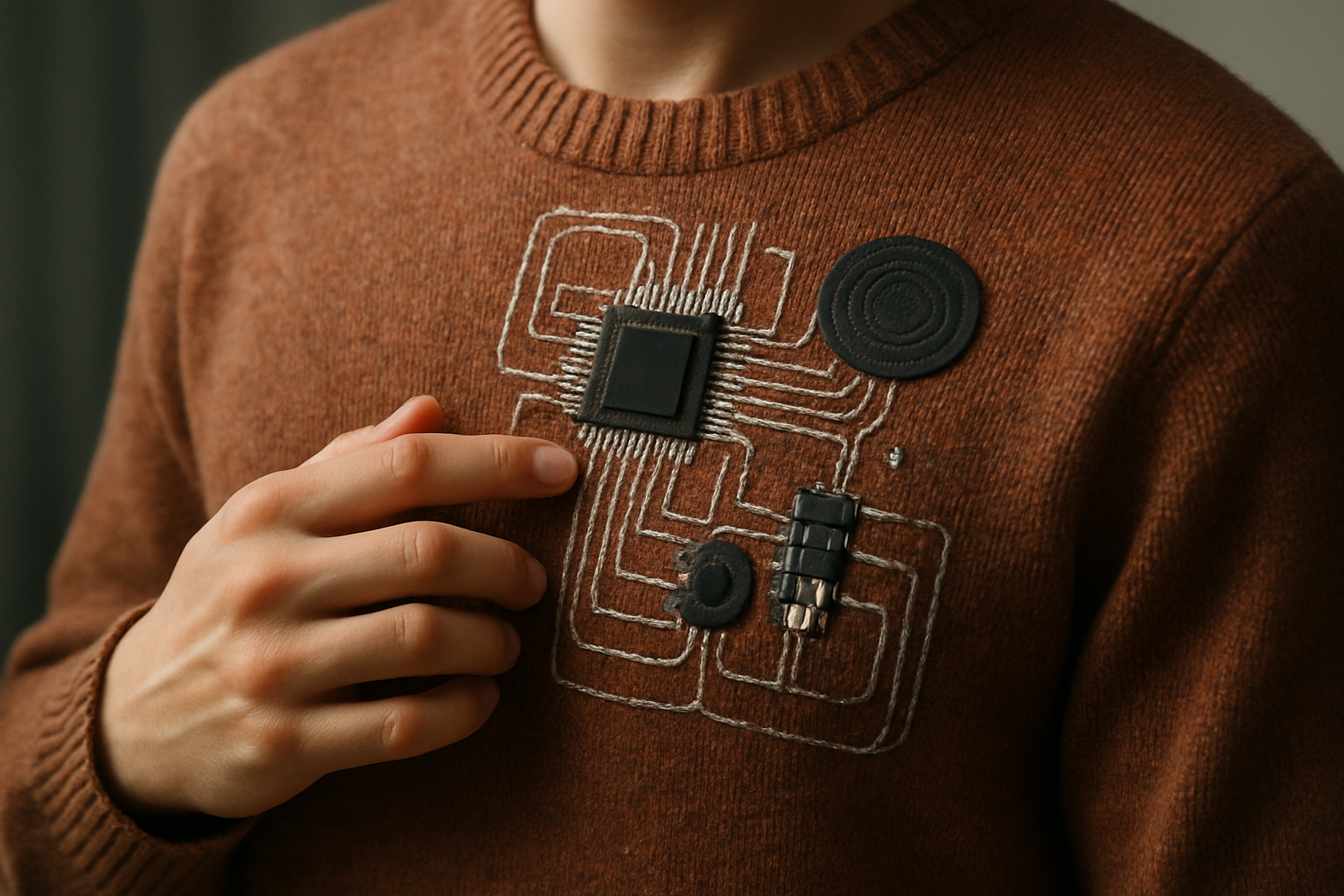

Technology Meets Tradition

The marriage of Kabuki with digital technology began cautiously in the early 2000s but has accelerated dramatically over the past decade. Leading theaters like Tokyo’s Kabukiza have incorporated projection mapping that transforms traditional wooden stages into dynamic environments, while maintaining the integrity of hand-painted backdrops and traditional set pieces. Motion capture technology now preserves the precise movements of aging master performers, creating digital archives that future generations can study and reference. Some productions have experimented with augmented reality elements that allow audience members to use smartphones to see historical context, language translations, and character information overlaid on performances. In Osaka, the experimental Digital Kabuki Lab has pioneered holographic representations of legendary performers from the past, allowing contemporary actors to share the stage with historical masters. These technological innovations aren’t merely spectacle—they’re carefully implemented to enhance storytelling while preserving the essence of traditional performance techniques that date back centuries.

New Audiences, New Approaches

The digital transformation of Kabuki has succeeded in attracting previously unengaged demographic groups. Recent data from the Japan Arts Council shows a 37% increase in attendance by viewers under 30 at technologically enhanced performances compared to traditional shows. Foreign tourists, previously intimidated by language barriers and cultural knowledge requirements, now comprise nearly 25% of audiences at select digital Kabuki productions that offer multilingual subtitle options and contextual information. The Shochiku Company, Kabuki’s primary production company, has developed abbreviated “Kabuki Highlight” productions that combine digital elements with traditional performance, creating accessible entry points for newcomers while still showcasing authentic techniques. University programs in Tokyo and Kyoto have established digital humanities initiatives focused on Kabuki, attracting students from technology fields who might otherwise never engage with traditional arts. Perhaps most significantly, children raised in digital environments show heightened interest in performances that blend familiar technological elements with the unfamiliar aesthetics of traditional theater, potentially securing future generations of Kabuki enthusiasts.

Preservation Through Pixels

Digital technology serves not just as performance enhancement but as a crucial preservation tool for Kabuki’s fragile legacy. The Kabuki Digital Archive Initiative, launched in 2015, employs high-definition video, 3D scanning, and artificial intelligence to document performances, costumes, and props with unprecedented detail. This work has particular urgency as many physical artifacts face deterioration and master performers age. The distinctive vocal techniques of Kabuki, including the musical narration style known as gidayū, are being recorded in specialized audio environments that capture nuances traditional recordings miss. Costume preservation efforts include microscopic digital scanning of centuries-old textiles, creating patterns that can be precisely reproduced when originals become too fragile for performance use. Most ambitiously, the Japanese Agency for Cultural Affairs has funded a comprehensive movement database documenting the precise kata (stylized movement patterns) that form Kabuki’s physical vocabulary, ensuring these techniques survive even if the chain of person-to-person transmission is interrupted. These preservation efforts represent not just technological achievement but cultural insurance for an art form designated as an essential element of Japan’s heritage.

Tensions and Philosophical Questions

The digital transformation of Kabuki has not occurred without controversy and resistance. Traditional practitioners, including several designated Living National Treasures, have expressed concern that technological elements distract from the human artistry at Kabuki’s core. Cultural critics question whether digitally enhanced performances remain authentic Kabuki or represent an entirely new art form that should be categorized differently. Some audience members report feeling disconnected from the immediacy and imperfection that characterize live performance when digital elements create too polished an experience. The philosophical debate extends to questions about the nature of performance itself—can a holographic recreation of a deceased master truly be considered Kabuki, or is it merely simulation? Economic tensions have emerged as well, with traditional craftspeople who create stage elements and props concerned about displacement by digital alternatives. The most productive conversations acknowledge these tensions while recognizing that Kabuki has always evolved in response to cultural changes, from its origins in women’s dances through adaptations during the modernization of the Meiji era. Finding balance between innovation and tradition remains the central challenge for Kabuki’s digital future.

Global Influence and Cultural Exchange

The digitization of Kabuki has facilitated unprecedented international cultural exchange around this distinctively Japanese art form. The Metropolitan Opera in New York hosted its first digital Kabuki production in 2019, combining traditional performance with holographic elements that made the elaborate staging possible in a non-specialized venue. European festivals including those in Edinburgh and Avignon have featured technology-enhanced Kabuki performances that attracted record attendance from audiences previously unfamiliar with Japanese theater traditions. Digital collaborations between Kabuki artists and international performing groups, including Beijing Opera companies and experimental Western theater troupes, have created hybrid productions that explore cultural commonalities and differences. Japanese video game companies have partnered with Kabuki theaters to create interactive experiences that introduce gaming audiences to traditional narrative structures and character types. These cross-cultural exchanges demonstrate how digital innovation can serve as a bridge between traditions rather than replacing them, potentially creating new global appreciation for an art form that once seemed inaccessibly foreign to non-Japanese audiences. As these collaborations continue, they raise intriguing questions about cultural ownership, appropriation, and the universal aspects of storytelling across different performance traditions.