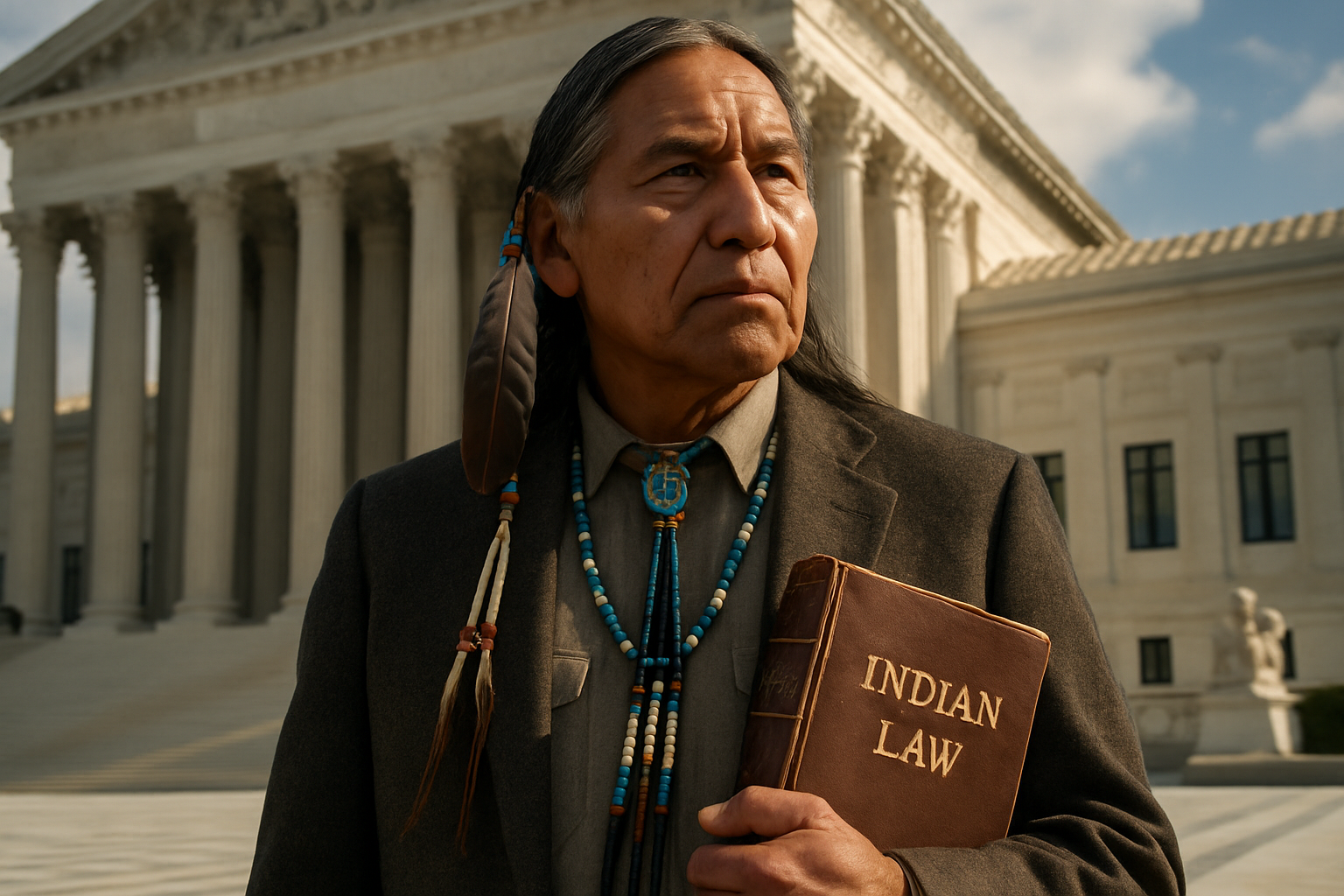

Tribal Sovereignty in Modern America: Legal Challenges and Opportunities

The intricate legal landscape of tribal sovereignty in the United States presents a fascinating study of constitutional principles, historical treaties, and evolving jurisprudence. Native American tribes occupy a unique position within America's legal framework—recognized as "domestic dependent nations" with inherent powers of self-government. This status creates complex jurisdictional questions that continue to shape federal Indian law. Recent Supreme Court decisions have significantly altered the boundaries of tribal authority, while economic developments from gaming to natural resource management have opened new avenues for tribal self-determination. Understanding tribal sovereignty requires examining both its historical foundations and contemporary challenges that tribes face in exercising their governmental powers.

The Legal Foundations of Tribal Sovereignty

Tribal sovereignty in the United States stems from the pre-constitutional status of Native American tribes as self-governing entities. The Marshall Trilogy—three Supreme Court cases decided between 1823 and 1832—established the fundamental principles governing federal-tribal relations. In Johnson v. M’Intosh (1823), the Court introduced the discovery doctrine, limiting tribal property rights. Cherokee Nation v. Georgia (1831) described tribes as domestic dependent nations, while Worcester v. Georgia (1832) recognized tribes’ inherent sovereignty and limited state jurisdiction over tribal territories. These decisions created the trust relationship between tribes and the federal government, wherein the United States has special obligations to protect tribal interests while acknowledging tribes’ right to self-governance.

The legal doctrine established through these cases recognized that tribes retain all sovereign powers not explicitly removed by federal statute, treaty, or Supreme Court ruling. This residual sovereignty includes powers to determine tribal membership, establish governmental structures, administer justice systems, regulate internal affairs, and exercise civil regulatory authority. However, through the plenary power doctrine, Congress maintains broad authority to limit or expand tribal sovereignty—a power that has been exercised extensively throughout American history, often to the detriment of tribal nations.

Criminal Jurisdiction: McGirt and Its Aftermath

The 2020 landmark Supreme Court decision in McGirt v. Oklahoma fundamentally reshaped criminal jurisdiction in Indian country. The Court held that much of eastern Oklahoma remains Muscogee (Creek) Nation reservation land for purposes of the Major Crimes Act. This ruling affirmed that Congress never explicitly disestablished the reservation, despite Oklahoma’s assumption of jurisdiction for over a century. The decision’s immediate impact required criminal cases involving Native Americans within these boundaries to be prosecuted in federal or tribal courts rather than state courts.

McGirt’s ramifications continue to unfold across Oklahoma and potentially beyond. The ruling has been extended to the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, and Seminole Nations, collectively covering approximately 43% of Oklahoma’s territory. This jurisdictional shift has placed significant strains on federal and tribal court systems, prompting calls for additional resources. Some legal scholars suggest McGirt could influence questions of civil jurisdiction, taxation, and regulatory authority. The decision represents a rare modern Supreme Court victory for tribal sovereignty, emphasizing that historical treaties remain legally binding unless explicitly abrogated by Congress.

Economic Development and Sovereign Immunity

Tribal economic development has become inextricably linked with sovereign immunity—the legal doctrine that protects governments from lawsuits without their consent. The Supreme Court has repeatedly affirmed that tribal sovereign immunity extends to commercial activities both on and off reservation lands. This protection has facilitated economic development through tribal enterprises including casinos, hotels, energy projects, and manufacturing facilities.

The Indian Gaming Regulatory Act of 1988 created the framework for tribal gaming operations, requiring tribes to negotiate compacts with states for certain forms of gaming. These operations have transformed many tribal economies, generating billions in revenue and creating substantial employment opportunities. However, sovereign immunity in the commercial context has faced increasing challenges. In Michigan v. Bay Mills Indian Community (2014), the Court reaffirmed tribal immunity for off-reservation commercial activities but noted that Congress could modify this protection. Similarly, in Lewis v. Clarke (2017), the Court distinguished between tribal immunity and individual immunity for tribal employees, holding that tribal employees sued in their individual capacity may not always invoke tribal sovereign immunity.

Environmental Sovereignty and Resource Management

Tribal nations increasingly assert sovereignty over environmental regulation and natural resource management within their territories. The Environmental Protection Agency’s 1984 Indian Policy recognizes tribes as the primary parties for environmental policy decisions affecting reservation lands. Several federal environmental statutes, including the Clean Water Act and Clean Air Act, contain provisions allowing tribes to be treated as states for regulatory purposes, enabling them to establish environmental standards and implement compliance programs.

Water rights represent a particularly critical area of tribal environmental sovereignty. The Winters Doctrine, established in Winters v. United States (1908), holds that when the federal government creates an Indian reservation, it implicitly reserves water rights necessary to fulfill the reservation’s purposes. These reserved water rights carry priority dates from when the reservation was established, often making them senior to other users’ rights in water-scarce regions. Recent settlements like the 2010 Crow Tribe Water Rights Settlement Act demonstrate how tribes are securing their water resources through negotiation rather than protracted litigation.

Future Directions: Self-Determination and Federal Reform

The path forward for tribal sovereignty involves strengthening self-determination while addressing historical injustices. The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, which the United States endorsed in 2010, provides an international framework supporting indigenous self-governance and cultural protection. However, meaningful implementation requires domestic legal reforms.

Several promising developments suggest potential directions for enhanced tribal sovereignty. The 2020 PROGRESS Act expanded tribal self-governance programs within the Department of the Interior, allowing greater flexibility in administering federal programs. The Native American Business Incubators Program Act provides resources for developing reservation economies beyond gaming. Additionally, the Tribal Law and Order Act of 2010 and the 2013 reauthorization of the Violence Against Women Act partially restored tribal criminal jurisdiction over non-Indians in domestic violence cases—addressing a jurisdictional gap created by Oliphant v. Suquamish Indian Tribe (1978), which had severely limited tribal authority over non-Indian offenders.

For tribal sovereignty to reach its full potential, federal Indian law must continue evolving away from paternalistic approaches toward genuine respect for tribal self-determination. This requires acknowledging tribes not merely as beneficiaries of federal programs but as governments exercising inherent authority. Through this lens, the future of tribal sovereignty represents not just a legal doctrine but a pathway toward healing historical wounds and allowing America’s first nations to flourish on their own terms.