Wabi-Sabi Interiors: Finding Beauty in Imperfection

The gentle curve of a hand-thrown ceramic bowl, its glaze slightly uneven. The weathered patina of a wooden table, telling stories through its scratches and marks. These aren't flaws to be hidden—they're celebrations of authenticity in the Japanese aesthetic of wabi-sabi. Unlike the polished perfection dominating contemporary design, wabi-sabi embraces the incomplete and impermanent. It finds profound beauty in modest simplicity, the marks of age, and natural processes. As our lives grow increasingly digital and detached from physical reality, this ancient philosophy offers a refreshing counterpoint—a chance to reconnect with materiality, impermanence, and the soulful quality of objects that bear witness to the passage of time.

Origins and Philosophy of Wabi-Sabi

Wabi-sabi emerged from Zen Buddhist teachings in 15th century Japan, representing a radical departure from the ornate aesthetics that preceded it. The term combines two distinct concepts: “wabi,” referring to the beauty of simplicity and quietude, often with a hint of rustic character; and “sabi,” describing the patina and dignity objects acquire with age and use. Early tea masters like Sen no Rikyū popularized these principles through the Japanese tea ceremony, using irregular, handmade vessels rather than perfect Chinese porcelain.

Unlike Western traditions that often prize symmetry, completeness, and permanence, wabi-sabi celebrates asymmetry, incompleteness, and impermanence. It acknowledges the transient nature of existence—nothing lasts forever, nothing is perfect, and nothing is truly finished. This philosophy doesn’t merely tolerate imperfection; it actively cherishes it as evidence of authenticity and life lived. The cracks in a ceramic bowl mended with gold (the art of kintsugi) don’t diminish its value but enhance it by highlighting its history and resilience.

In our contemporary culture of disposability and endless pursuit of the new and flawless, wabi-sabi offers a profound alternative—an aesthetic that honors materials, craftsmanship, and the natural processes of aging and weathering.

Core Elements of Wabi-Sabi Interiors

Implementing wabi-sabi in home design begins with embracing natural, minimally processed materials. Unfinished or lightly finished wood that reveals its grain and knots; stone with visible variations in color and texture; clay, paper, and natural fibers that display their inherent characteristics—these materials form the foundation of a wabi-sabi interior. Their imperfections aren’t hidden but appreciated as part of their unique identity and charm.

Color palettes in wabi-sabi spaces tend toward muted, earthy tones—the colors of clay, stone, aged wood, and natural dyes. These aren’t flat or lifeless colors but complex hues with depth and subtle variation. Think of the many shades visible in a piece of weathered driftwood or the variations in a mud-plastered wall.

Textures play a crucial role, providing tactile interest and visual depth. Rather than smooth, machine-perfect surfaces, wabi-sabi interiors feature handcrafted textures: the slight unevenness of hand-plastered walls, the rough weave of natural textiles, the irregular surface of hand-formed pottery. These textures invite touch and engagement, creating spaces that appeal to all senses.

The wabi-sabi home embraces negative space—”ma” in Japanese—allowing rooms to breathe rather than filling every corner. Objects are chosen with intention, valued for their utility, emotional resonance, and aesthetic appeal rather than as status symbols or decorative fillers.

Collecting and Curating for Wabi-Sabi Spaces

Creating a wabi-sabi interior isn’t about shopping for a particular style but developing a more mindful relationship with objects. Instead of mass-produced items designed to look perfect (until they inevitably break or become dated), wabi-sabi homes feature objects with integrity—those made with care by human hands, from quality materials, that will age beautifully rather than simply deteriorate.

Handcrafted ceramics stand at the heart of many wabi-sabi collections. Look for pieces made by local artisans showing the maker’s hand—slight asymmetry, visible throwing lines, glaze variations. These imperfections aren’t manufacturing defects but signatures of human creation, each piece unique rather than identical.

Textiles in wabi-sabi spaces favor natural fibers with minimal processing: raw silk, unbleached cotton, rough linen, hand-loomed wool. These materials not only connect us to ancient traditions of making but also develop character as they age—linen that softens with each washing, wool that develops a beautiful patina with use.

Wooden furniture and objects might show knots, grain irregularities, or even cracks that have been stabilized rather than disguised. Reclaimed wood pieces carry particular significance, their prior lives visible in marks and weathering that tell stories no new material can.

The wabi-sabi approach to collecting values fewer, better things over abundance. Each addition should serve a purpose—functional, aesthetic, or emotional—and bring genuine joy rather than momentary satisfaction. This thoughtful curation naturally leads to more sustainable consumption patterns, as objects are chosen for longevity and timeless appeal rather than passing trends.

Creating Atmosphere Through Wabi-Sabi Principles

Lighting in wabi-sabi interiors tends toward the soft and natural—diffused daylight filtering through shoji screens or simple curtains, complemented by warm, localized artificial lighting rather than harsh overhead illumination. This gentle approach to lighting creates an atmosphere of calm and intimacy while highlighting the texture and depth of natural materials.

The wabi-sabi home engages all senses. Beyond visual aesthetics, consider the subtle scent of beeswax polish on wood, the cool smoothness of stone underfoot, the gentle sound of a bamboo wind chime, or the weight of a hand-thrown ceramic cup in your hands. These sensory experiences ground us in the physical world, a powerful antidote to our increasingly virtual lives.

Seasonality plays an important role in wabi-sabi interiors, acknowledging the changing cycles of nature. Simple seasonal adjustments—branches of autumn leaves in a ceramic vessel, lighter textiles for summer, the scent of woodsmoke in winter—connect living spaces to the natural world and its rhythms.

Plants and flowers in wabi-sabi spaces aren’t perfect hothouse specimens but natural arrangements that might include a few weeds or grasses, showcasing the beauty of ordinary flora. They’re often displayed in simple, unassuming containers that complement rather than compete with their natural beauty.

Integrating Wabi-Sabi with Modern Living

While rooted in centuries-old philosophy, wabi-sabi isn’t about recreating historical Japanese interiors or rejecting all aspects of modern life. Instead, it offers principles that can be thoughtfully integrated into contemporary spaces to create homes with greater depth, authenticity, and tranquility.

Modern wabi-sabi might mean choosing a handcrafted dining table for family gatherings but pairing it with comfortable contemporary chairs. It could mean complementing clean-lined architecture with artisanal details—hand-plastered accent walls, handmade tiles in the kitchen, or custom wood details showing the craftsperson’s mark.

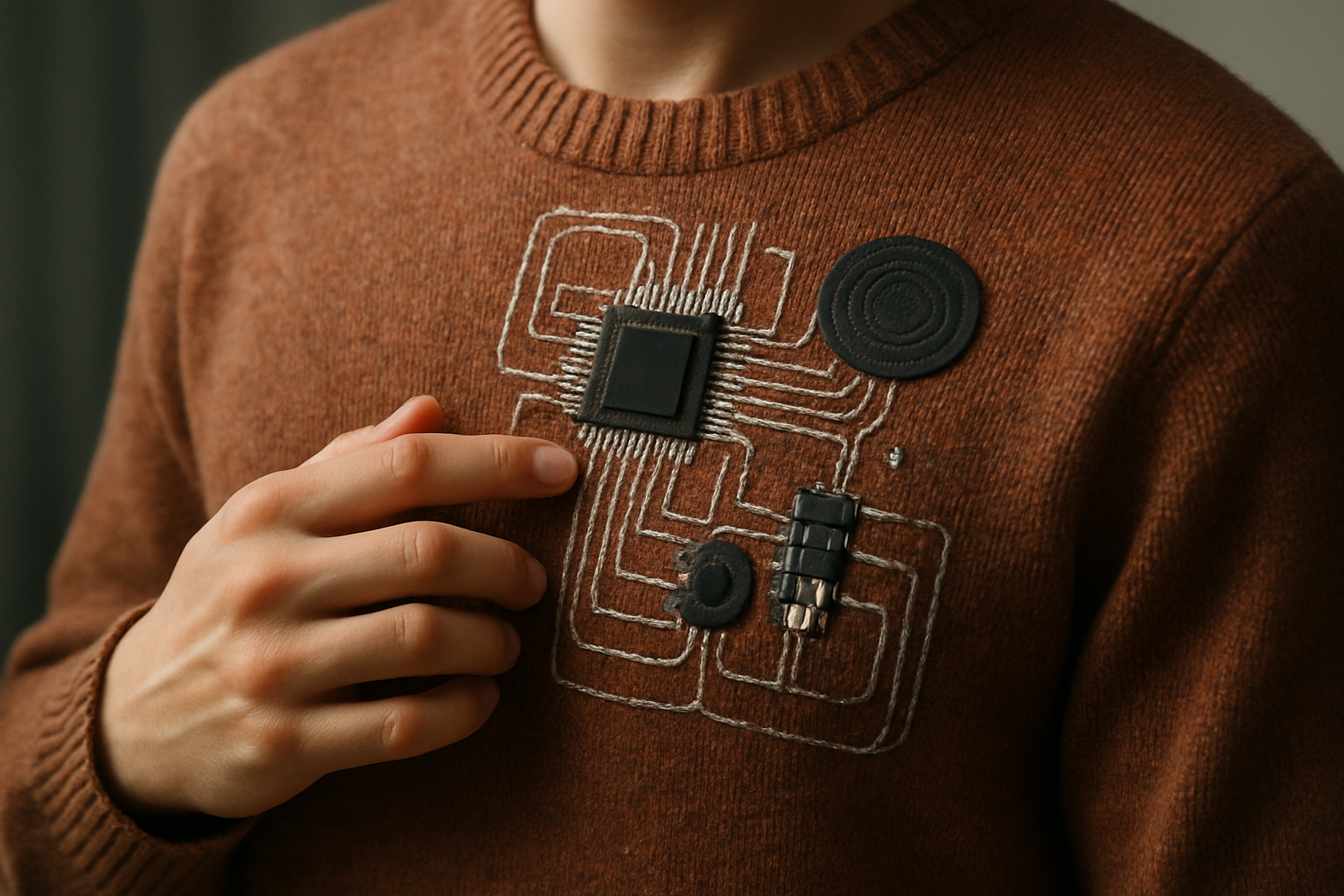

Technology needn’t be banished but can be mindfully integrated. Consider natural materials for tech accessories, like wooden charging stations or leather cable organizers. Create intentional spaces for digital devices that allow them to be put away when not in use, helping maintain the calm atmosphere of wabi-sabi interiors.

The environmental benefits of wabi-sabi design align perfectly with contemporary sustainability concerns. By valuing longevity, repairability, natural materials, and craftsmanship, wabi-sabi interiors naturally reduce consumption and waste. Appreciating patina and aging means fewer replacements and redecoration projects driven by passing trends.

Perhaps most importantly, wabi-sabi offers psychological benefits particularly relevant to our current moment. In a culture that often promotes perfectionism and its accompanying anxiety, wabi-sabi’s embrace of imperfection can be profoundly liberating. It encourages us to find beauty in reality rather than an impossible ideal, to accept the natural cycles of growth and decay, and to create homes that feel authentic and soulful rather than staged for approval.